Most in the industry have never experienced anything like the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. This global disruption has affected supply chains across every industry, and in the same breath, destroyed and heightened demand for an array of products and services. It has also forced companies to rethink their manufacturing dependence on a single country. Consider this: the term “reshoring” has been spiking in Google search terms, and one-third of companies have or plan to move their supply chains out of China by 2023.

COVID-19-induced supply chain disruptions in China, which has led to the inability for the United States to receive critical shipments of personal protective equipment (PPE), brought the conversation mainstream. However, there have been growing business reasons to have a diversified strategy well before the pandemic—rising labor costs, human rights issues, tariffs and geopolitics all play a role.

But, what will it really take to reshore or nearshore to Vietnam, Thailand, Mexico, or right here in the United States? And, what can companies do to ensure supply chain resilience?

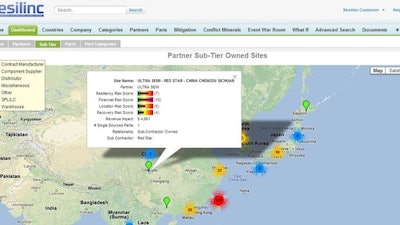

The journey to a diversified, risk-adjusted supply chain network strategy begins with mapping. Multi-tier visibility into the entire supply chain – including second- and third-tier suppliers –can help identify the most optimal supply chain design. This is because mapping provides a complete picture of the current supply chain, as well as the alternate sites that are available or possible, where parts could be sourced. Knowing the options can allow experts to weigh different cost and lead time considerations to then optimize the location that offers the best balance of cost and risk.

The visibility mapping provides may make it possible to move your supply chain without having to switch suppliers. Imagine if you mapped your Tier 1, 2 and 3 suppliers in China? What you’d likely find is that 30% of them have manufacturing sites outside of China. Instead of onboarding new suppliers, which is extremely labor and cost intensive, you’d be able to easily shift to an alternate location with minimal disruption. In this case, the value of the map will be greater than the cost and time to develop it.

While mapping is a smart first step, any decision of this kind should be preceded by carefully weighing the risks and costs of such a move. There are, after all, many reasons for China to have earned the nickname, “The World’s Factory.” Manufacturers were first drawn to China because of the opportunities to lower costs. But, over the years, China has built up one of the strongest and most technologically sophisticated industrial ecosystems in the world. Its firms are critical suppliers to global companies in pharma/biotech, consumer electronics, automotive, energy, apparel and many other industries. China has a huge skilled workforce and a shipping and logistics infrastructure that is unmatched anywhere on the globe. These advantages should be weighed against the true costs and risks of any reshoring or nearshoring moves.

In some industries, the process of qualifying and vetting a new supplier as part of a strategy to nearshore or re-shore supply chains can be very labor and time intensive. Consider this: for healthcare product companies, going through the required FDA approval for a new supplier can take up to two years. In consumer electronics and other high technology sectors, the performance of many raw materials and components is very sensitive, so extensive testing and validation is needed before these items can be sourced through a new supplier without significant risk to the performance of end-use products.

In the apparel industry, where brands can source essentially the same products from many different contract manufacturers, it will be much simpler and less expensive to find new suppliers outside China. Additionally, in these industries, it is possible to shape demand by offering discounts or different products if a disrupted product is not available. However, it can be difficult to truly “decouple” an apparel supply chain from China because of the position its companies have achieved in manufacturing textiles, zippers, fasteners and other items that a “cut-and-sew” factory in another country still relies on the produce garments. For example: a Wall Street Journal story in March reported on a 500-employee garment factory in Bangladesh that was disrupted when half of its 16 Chinese supervisors were quarantined back in China. This is why mapping is critical – knowing where the second or third tier suppliers are located can help inform not only the supply chain network design strategy, but how much inventory to hold for which items, to provide resilience and supply continuity on an ongoing basis.

Even though wages in China are rising and the demographics of an aging population makes labor availability challenging, Chinese workers are still difficult to beat in terms of availability and manufacturing skills. The hourly wage for Chinese workers is still very low, and availability of labor is very high across many industries and skill sets, and there is a significantly higher pool of skilled labor in China compared to developed countries.

With our current high unemployment rate in this country, many companies, including foreign firms supplying U.S. customers, are looking more favorably on building domestic manufacturing capacity. But, while it will be easier for them to hire workers than it would have been a year ago, most U.S. workers have no experience outside of service industries and would therefore require significant training for today’s manufacturing processes. Therefore, industries which are still fairly labor intensive and not conducive to automation might find re-shoring to be a cost prohibitive strategy. Processes or products that can be automated to a great degree are generally good candidates for re-shoring.

Many companies are also looking at Mexico as an alternative. Mexico is already a large importer to the United States; shipping costs can be significantly less, and tariff advantages can be found in the recently ratified United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). But, compared to many Asian countries, such as Vietnam, Malaysia, India, and Thailand, Mexico is still an expensive country in which to operate. In evaluating total landed costs of a sourcing shift, the advantages of other Asian countries should be given due consideration.

Developing countries like Vietnam offer a strong alternative, but China has streamlined many operational challenges to make it easy to establish manufacturing there, compared to other alternative countries. One should also consider that no country or location is really risk free. Every location brings with it a host of different and unique challenges and vulnerabilities. These should be thoroughly examined by reviewing historical disruptions, events and studying how the local and national government reacted to help companies resume operations. The government’s ability and track record to mobilize, respond and help businesses resume operations is a critical factor when evaluating different countries’ risk profile.

There is no single supply chain network design strategy that applies across all industries. Within a company’s product portfolio, different products might have unique requirements. Margins, customer demand locations, product life cycle, substitutability and customer preferences are critical variables that are important to examine in determining the right strategy. The one common theme across all industries, products, use cases and supply chains is that the journey begins with mapping.

Interestingly, as unprecedented as this time is, the lessons and conversations related to supply chain dependence and resiliency are not new. In fact, they are same ones that were talked about in earlier disasters—the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan and Hurricane Maria in 2017 are two examples (albeit on a smaller scale). While there can be major benefits in reshoring or nearshoring parts of a supply chain currently based in China, supply chain and procurement professionals need to make a clear-headed analysis of the risks, costs and benefits in order to ensure that such decisions are made for long-term competitive advantage rather than in response to the trends of the moment.