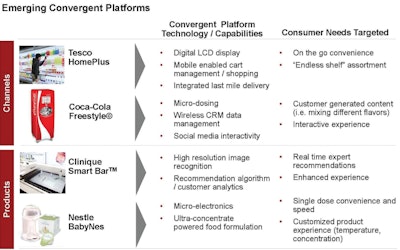

Traditional Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG) companies and retailers are rethinking their critical segments. With escalating pressures to continually provide innovative market offerings while simultaneously demonstrating sustainable, profitable growth, it’s no surprise that these CPG and retail companies are thinking more like their consumers. They are challenging the traditional topics as basic as how to define a channel and the nature and value of a product. As a result, these CPG and retail value chains lead progressive companies to develop new convergent products and channels which combine cross-disciplinary technologies and capabilities to create compelling value propositions.

Real-time convergence scenarios

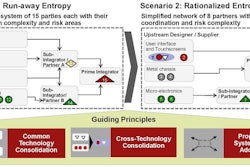

Powerful things begin to happen when commercial offerings imitate consumer lives. Convergent platform innovations offer significant opportunities and present unique challenges, most notably the need to effectively orchestrate a number of outsourced, industry-spanning, cross-disciplinary capabilities such as complex high-tech product engineering, rapid lifecycle technology design and managing a complex global partner base. Unlike traditional outsourcing, where the activities are often non-strategic, orchestrating convergent platform innovation is significantly more complex as depicted in Figure 2. But it’s not impossible.

After limited trials earlier in the year in Philadelphia and Chicago, Peapod LLC—in partnership with Barilla, Coca-Cola, Kimberly-Clark, Procter & Gamble (P&G) and Reckitt Benckiser—announced this past October that it would open over 100 “virtual grocery stores” in commuter rail stations in Boston, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C. and Chicago.

The idea is simple. Commuters armed with iPhones, iPads or Android phones just scan bar codes of the products in the virtual grocery aisles within billboards displayed on train platforms for home delivery. Peapod’s East Coast virtual stores’ ads feature household products, food & beverage (F&B) items and beauty care products. The company expects half its orders to come through mobile devices by 2014—good news since the typical iPad shopper’s ticket is higher than the typical Peapod ticket of $150.

The program mirrors Tesco’s Home Plus’ “subway store” offering in South Korea. Launched in June 2011, the subway program increased Tesco’s sales by 130 percent in just three months.

Whether in Seoul or SoHo, the concept of “taking shelves to where the customers are” requires retailers to successfully orchestrate a complex set of capabilities—from software support of mobility-enabled shopping to “last mile” warehousing and fulfillment issues in metro markets.

Coca-Cola’s Freestyle beverage dispensing system is another example of a successful convergent platform. Freestyle machines allow customers to mix and match over 100 individual Coca-Cola flavors through a wireless enabled touch-screen interface. The Freestyle platform offers a direct-to-customer channel for testing new products and interacting with customers. As in the Peapod and Tesco examples, Freestyle requires Coca-Cola to orchestrate non-traditional capabilities including micro-dosing technology from the medical device industry and precision automotive metal chassis building. Both examples demonstrate the opportunity and game-changing nature of convergent platforms.

Our experiences working directly with global CPG and retail companies and across industries engaged in complex innovation outsourcing such as consumer electronics and defense taught us that leading orchestrators consistently outperform their peers. On average, they achieve development and launch milestones 25 to 50 percent faster; and enjoy 20 to 40 percent cost advantages; and have a higher likelihood of sustained differentiation.

Thus, outsourcing convergent platform innovation requires the presence of five elements of success (click here to see the first two elements).

Success Driver 1: Creating the Right Orchestration Organization

Companies which embark on ambitious innovation initiatives often find that demands for short-term results lead to downstream complications including the loss of centralized decision making; misalignment of necessary skills; and conflicting agendas. Establishing the right orchestration organization and management structure upfront becomes even more critical in environments where the development process requires coordination across multiple external entities and organizational boundaries.

Convergent platform innovation is similar to small-cap, early-stage start-up efforts, often ill-suited to the management and cultural style of larger and more hierarchical organizations.

Large cap leaders in industries characterized by complex outsourcing—like consumer electronics and aerospace—adopt an “incubator” structure as a proven organizational strategy. An incubator organization structure can foster and enable the right mix of rapid decision making; championing of an entrepreneurial mentality; and the development of a risk taking culture required for success. As shown in Figure 3, establishing stand-alone objectives and mandates, backed by strong executive leadership, is key to making an incubator model work. Autonomous decision-making is needed across departments from identifying customer requirements; to feature definition and design; to supply chain and manufacturing partnership management. Incubators also require dedicated resources and budgets to leverage personnel and expertise from multiple functional units with shared metrics and incentives.

An incubator approach opens the door to organizational and governance alignment for rapid experimentation, appropriate risk taking and outside the box thinking.

For example, a consumer healthcare client seeks growth through diversifying into home-use health and beauty devices. But the company ends up squashing its R&D team’s most innovative ideas at the concept stage and missed development timelines for those ideas that made it to prototyping. As a result, poor organizational alignment created a failure cycle.

Without senior executive commitment, even the most promising ideas failed to receive adequate funding or hit internal rate of return targets. The few prototypes managing to make it to production—such as a promising light-based home-use wrinkle remover—were delivered by managers lacking shared incentives and trapped in traditional metrics. R&D engineers were focused on safety and functional features without involving contract developers early on to ensure cost-effective production. That led contract developers—focused on speed-to-market instead of balanced performance—to deliver a differentiated, but far too costly, product that failed to meet conservative payback goals versus risk profiles and quite naturally, died off.

Leading orchestrators complement the right organizational structure by ensuring they install the right management team to mitigate risks and delays. The majority of project delays and risks to distributed innovation initiatives occur at coordination “boundaries” where critical decisions are made and critical activities handed off from one group to another. These boundaries come in two forms: decision-making boundaries where sub-optimal trade-offs are made between competing options; and activity-coordination “boundaries” when work is passed from one firm in the value chain to another. Establishing an effective management team with necessary boundary-spanning competencies significantly improves decision making and goes a long way toward ensuring success.

Effective orchestration managers are often generalists with diverse functional expertise as well as relevant technical experience of the underlying key platform technologies. In addition to establishing the right organizational structure and installing the right team, best-in-class orchestrators broker and maintain effective partnerships across the innovation lifecycle and along the value chain.

Success Driver 2: Building and Evolving Effective Partnerships

Outsourced partnerships are defined by their underlying integration activities—a holistic set of interrelated roles, processes and management of upstream supply chain activities. During ideation, these activities include defining consumer-centric platform features and design. During development, they include activities like sub-system prototyping and testing manufacturability. One defining capability of leading orchestrators is their ability to both establish the right partnership structure and then evolve it through changing objectives and market dynamics when outsourcing critical integration activities across the value chain and innovation lifecycle.

Building the right partnership—Leading orchestrators establish effective outsourcing partnership by defining correct spans of control in coordinating and managing upstream value chain activities with key partners and injecting the appropriate level of competition. Maintaining excessive span of control forces orchestrators to operate in areas beyond their core competency and leads to unfocused execution. Giving up too much control to suppliers can threaten intellectual property (IP) and promotes development of undifferentiated solutions.

Defining the appropriate level of control requires systematic assessment of the underlying risk versus opportunity considerations as depicted in Figure 4. The orchestrator must objectively decide if it has the necessary in-house expertise to actively manage upstream sub-contractors and integration activities or if it should delegate to its key partner. Also, the degree of contractual and incentive mechanisms protecting against IP risks is also a consideration on the degree of retained control vs. delegating to partners of upstream value chain activities.

To illustrate, Apple consistently employs a tight span of control of its outsourcing activities even in “non-core” production logistics activities. Rather than relying on external manufacturing partners to turn-key coordinate new product activities, Apple manages key upstream supply chain activity points such as factory-to-port logistics to guarantee end-to-end IP security and zero product leakage. As illustrated on the vertical axis on Figure 4, Apple’s need for IP security and launch secrecy demanded a tight span of control across most of its outsourced activities for the iPhone platform.

Establishing the right level of competition is the second skill in defining right partnerships. Best-in-class orchestrators systematically manage their key development and integration efforts to enable increased competition across the lifecycle. As depicted along the horizontal axis in Figure 4, orchestrators enable competition through ensuring modular design and minimizing asset specificity, or dependency on external partner for specific capital and/or technology know-how.

Increased competition not only ensures optimal costing but also increases capacity flexibility and risk redundancy. Cisco is an example of a leading orchestrator who systematically guides platform development trajectory to enable competition. While early stage prototyping may rely on a key technology partner with specific know-how or capital assets, Cisco aggressively pursues rapid iterations of redesign enabling a more modular design as well as increase sub-component substitutes in moving from prototyping to production. Cisco also employs different strategies to secure critical IP rights—such as paying an upfront premium to secure all IP ownership; or splitting IP ownership by market application and software versus hardware with its key partners to protect core commercial IP.

Evolving the right partnership—Savvy orchestrators evolve partnership structures to ensure sustained outsourcing performance since changes in the organization strategy and external industry dynamics necessitate redefining span of control and level of competition.

Let’s say an orchestrator makes a strategic shift to develop deeper in-house bench expertise on up-stream value chain capabilities. Over time, this leads to an increased span of control in upstream value-chain coordination and management to reduce external dependencies.

In an effort to cut cost in the 1990’s, automotive OEMs over-indexed on outsourcing key component prototyping and manufacturing to Tier One suppliers in a turnkey model, leading to loss of development control and increasing costs. In recent years, many OEMs have invested in the in-house expertise required to regain control of upstream component of outsourcing management and coordination activities.

Other orchestrators, like Redbox, delegate increasing scope of activities to external partners as market place alternatives offer better efficiencies, scale and flexibility compared to internal capabilities. The DVD kiosk innovator designed and prototyped its first generation platform in-house but quickly realized that it could accelerate redesign lead time and production ramp-up efficiencies by leveraging the know-how and scale of Get-A-Movie, their design partner and contract OEM Flextronics.

Similar to evolving its span of upstream value chain control, orchestrators can also change the degree of partnership competition by moving from a single turnkey partner to multiple partners, especially as integration activities and underlying technologies become more commoditized across the development lifecycle. Several years ago, a leading consumer healthcare company moved to a dual-contract design and manufacturing model for its innovative diabetes-monitoring platform once it had erected strong patent protection and realized that several underlying proprietary technologies are becoming commoditized, allowing them to increase supplier competition and flexibility at minimal IP risk.

Figure 5 summarizes the various market and structural factors triggering a need for evolving partnership structure across key outsourced activities.

It is also important to ensure incentives and contract structures align as partnership structures evolve. Defining a fixed fee contract structure with product design firms during the prototyping stage is sub-optimal since it encourages the design firm and its upstream suppliers to cut cost and protect margins, rather than encouraging the desired behavior of rapid design and innovative experimentation. Similarly, employing a cost-plus contract with key manufacturing partners during the platform production ramp-up stage leads to excessive cost inefficiencies as contract manufacturers are incentivized to over-index on quality and speed over balancing with long-term production costs and efficiencies.

Success Driver 3: Managing Value Chain Entropy

Distributed product development environments can be entropic as well as complicated. And unmanaged entropy can create untold issues.

When Sony orchestrated the design and development of its Blu-Ray DVD-enabled PlayStation 3 console, it underestimated the complexity of the increasing pile-on of Blu-Ray design partners, component manufacturers and software integrators involved in rolling out a standardized specification enabling seamless production integration and ramp-up. The resulting systemic entropy delayed the global launch by over a year, giving the competing Microsoft Xbox a unique opening to steal market share.

Checking value-chain entropy requires unique skill sets and aggressive, hands-on management or the resulting process can destroy a product and, over time, the innovation ecosystem. Unchecked value chain entropy leads to an accumulation of extraneous assets and unnecessary capital demands. It increases the likelihood of assigning assets to wrong roles, sub-optimal system performance and slows down and/or impedes decision making as overly complex networks prevent external signals from accurately reaching the orchestrator. Increasing entropy overwhelms commercial ecosystems leading to complete platform failures. The bottom line: entropy creates more points of unpredictable disruption and failure.

The orchestrated retail/CPG space

In a commercial environment where competition continuously escalates and consumer needs are rapidly evolving, CPG companies and retailers continue to struggle to bring game-changing offerings to market to cater to a sophisticated, fragmented and increasingly demanding customer base—a base whose product and shopping options expand on a daily basis.

Effective convergent channel and product platforms are critical to achieving long-term market relevancy and success in this tight margin, increasingly technology-driven market. Future leaders will be those companies that are willing to shatter traditional product sourcing and innovation paradigms and become skilled orchestrators.