One needn’t look hard to find cautionary tales of companies that fail to understand the cost to serve a market. It’s a danger that’s growing.

Just this year, we saw considerable news coverage of manufacturers forced to pull out of critical markets. LG Hausys Ltd., a building materials subsidiary of Korean conglomerate LG Chemical Ltd., pulled out of PVC profile manufacture, citing low profitability, in Russia. Nintendo Co. Ltd. stopped selling consoles and video games, citing high import taxes and other costs, in Brazil. And retail giant Target Inc. pulled out of Canada after incurring huge losses since it entered the country in 2013.

In 2012, Japanese car maker Suzuki Motor Corp. exited the United States after nearly three decades of business. Its U.S. subsidiary posted a loss of $15.8 million that same year.

With many established markets running stagnant, companies are looking to expand into new and emerging regions to boost sales. But companies often don’t know what that expansion costs. The true cost to serve a market is essential information that’s used strategically to make good business decisions. The problem is, most companies not only don’t know this figure, they’re completely unequipped to determine it.

Let’s take a closer look at why:

1.) Lumping the Unknown into Other Costs

Any mismatch between expected costs and actual costs should be explainable—in theory, at least. Either the expectation needs to change or some part of the process needs to be fixed. In reality, however, that isn’t happening. It’s becoming common practice to just buffer the expectation—throw an extra 35 percent into other landed costs and your expectation magically gets close enough to real spend that nobody really notices. But does simply labeling something that you don’t understand solve your problem? No. For a while, when profits were high, turning a blind eye didn’t matter as much. Now, with constantly thinning margins, failure to crack open the black box of other costs is unacceptable.

2.) Not Thinking Strategically in Terms of Service

Cost to serve can be viewed passively or actively. If you view it passively, then cost to serve boils down to, “I made a decision; what does that decision cost?” It’s passive because the relationship between cost and decisions is pretty much one way. Sure, small tweaks to decisions sometimes happen if costs run too high, but for the most part, they are miniscule changes. Actively approaching cost to serve means considering the entire cost of service: “Here are all the possible things I can do for my customer. What are their implications?” That active approach includes figuring out who has the power to make decisions and how often they can make them. For instance, when you expedite an order for a high-priority customer, it has both short- and long-term cost implications. Is that decision made by the warehouse worker, the manager or by pre-established strategic rules? The answer may not be set in stone. But an active approach to cost to serve gives you more information and more choice than a passive one.

3.) Misplaced Data

External supply chains often contain the very data companies need to determine their cost to serve a market—somewhere. The problem is most companies can’t find that data. Even if they could, many wouldn’t know what to do with it. The issue is exacerbated because various supply chain partners each have pieces of the puzzle. Something would have to unify all their information, interpret it and then draw conclusions. Most supply chains aren’t technologically equipped to engage in this sort of end-to-end big data analytics and communications. Information between partners hardly gets shared, and when it does, it’s often through disorganized methods like Excel spreadsheets buried in seas of email.

4.) Dismissing Granularity Because of Extreme Notions

Companies often think that getting more specific information requires a herculean effort. It’s easy to think that way because a lot of restructuring usually ends up being the expensive rip-and-replace kind. For some businesses, that type of investment hardly seems worth the effort, especially when you consider that initiatives like activity-based costing can be incredibly time-consuming with sometimes little benefit. But getting a handle on cost to serve a market doesn’t require tearing out entire accounting processes or going after needles in haystacks. Most data already exists somewhere in the supply chain. Gathering it to offer insight doesn’t mean scrutinizing ledgers to account for every last penny. It just requires the right information infrastructure.

If the data on cost to serve is already there, but scattered and buried across the supply chain, then the trick in how to unearth it. But there’s relief in realizing that a fundamental business problem—losing money in a new market—can be translated into a technology problem. And technology problems can be solved.

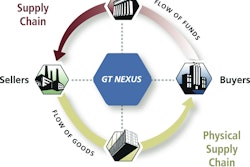

In this case, with cost to serve, the solution involves putting all the data that exists between different supply chain partners in one place, so you can analyze it. Cost-to-serve information may be scattered in bits and pieces between manufacturers, suppliers, logistics services providers, ground transportation, ocean carriers, and internal enterprise resource planning (ERP) record systems. How do you gather data from all these partners, combine it and tell a story about cost to serve?

Manufacturers may find that sharing information conveniently with their supply chain partners enables a lot of powerful business actions. Some of these include mitigating risk, maneuvering around unexpected disruptions, creating innovative payment strategies, and allocating inventory dynamically and efficiently. As a result, manufacturers are now adopting technology that enables sharing information more easily with suppliers. But beyond that, it lets them operate tightly as networks of businesses. Underpinning that technology is the cloud—a solution that’s easy to deploy, quick to scale, and capable of providing robust functions without demanding intrusive infrastructure changes.

Cloud-run networks can tackle cost to serve in a few interesting ways. First, by aggregating disparate data, they can provide a good picture of what all the costs are in a market. They also allow businesses to think strategically about what it costs to serve a particular market. For instance, the highest indirect cost businesses face is the cost of transporting goods. In markets like Canada, or Nigeria or Vietnam, you can do more than just figure out how much you’re paying. By connecting all your supply chain partners, you can actually coordinate with them to optimize transportation to fit your business goals.

Past transportation management systems (TMS) optimized transport around single partners. Cloud-run networks can offer TMS that optimizes globally for many partners. And it’s exactly that kind of active cost management that’s going to be the key to avoiding expensive, unpleasant surprises in new markets.

LG, Nintendo and Suzuki stand out as just some examples of a problem manufacturers are going to continue to face over the coming years. They’d be wise to learn these lessons and put themselves in a better position. Because what you don’t know can kill you. And withdrawing from a market isn’t a good way to go out. So start shining a light on your cost to serve.