Modern procurement is a whole new ballgame and the rules of the game are changing. The ongoing disruption caused by COVID-19 is only one example of how interconnected and volatile markets are accelerating focus on the function. Add in sovereign debt defaults, natural disasters, international terrorism, port slowdowns caused by labor disputes, and inadequate transportation infrastructure, and you’ve got a truly challenging environment for procurement professionals around the world. There’s a new set of rules around what procurement is procuring. Sourcing for services has exploded, and many organizations are shifting their strategy towards purchasing skills and processes. Moreover, the way to “win” at procurement is evolving as organizations increasingly abandon old school approaches like price squeezing and shifting risk onto suppliers in favor of more sophisticated, collaborative, win-win sourcing business models.

Organizations need all-star procurement teams to compete in this environment. However, recent research by APQC finds that many are struggling to scout external talent and to prepare in-house talent to step up to the plate. APQC surveyed 204 global procurement professionals, conducted interviews with procurement professionals around the world, and worked with the University of Tennessee and subject matter experts Kate Vitasek, Bonnie Keith, and Emmanuel Cambresy to learn about the current state of talent development and the future skills needs of the function. The quantitative and qualitative research collectively adds up to a compelling reality: Procurement talent development is not adequate in developing the most important skills for the future.

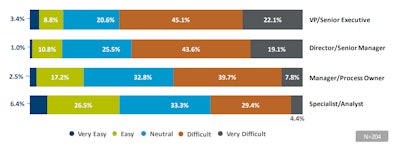

One out of three survey respondents said it’s difficult to secure qualified external talent even for entry-level procurement positions. The challenge increases as you go up the levels, with two-thirds of organizations reporting that it’s difficult to hire for VP and senior executive roles in the function. Difficulty of Recruiting Qualified External Professionals for Procurement

Difficulty of Recruiting Qualified External Professionals for Procurement

Why the challenge? Procurement lacks the clear development pathways of other professions, which makes it harder for young professionals to find their place and grow into the leaders of tomorrow. For example, if you like numbers you can study accounting, find an entry-level accounting position, earn your CPA, and work your way up to a public accountant, controller, or even CFO role. But with procurement, it’s not so straightforward.

Sadly, most newcomers enter the profession with backgrounds in general supply chain, business administration, finance, or accounting. And then, many don’t stick around because they see procurement as a stepping stone to other careers. As Michael van Keulen formerly of lululemon atheltica explains, “People like procurement because they get to be involved with a bunch of different, cool things, but then they leave and go do something else.” When you consider the fact that procurement and sourcing courses are often a small piece of a broader degree program, it’s no wonder young professionals don’t see procurement as a viable career path.

Credentialing offers one potential solution to the challenge, but unfortunately, the results often fall short of organizations’ expectations for on-the-job results. Almost 41% of those surveyed by APQC said that credentials had no impact on employees’ effectiveness and performance. This does not mean that credentials have no value at all—they are vital to help procurement professionals learn and stay abreast of job-specific knowledge and skills. The problem is, most in-demand procurement skills are not job-specific.

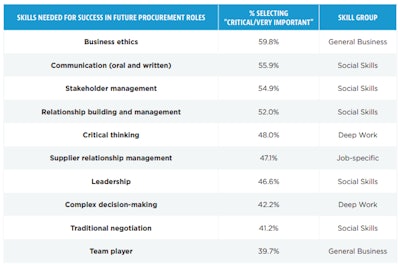

When APQC asked procurement professionals to identify the skills most needed for success in future procurement roles, only one of the top 10 skills (supplier relationship management) was job specific. Social skills—like communication, stakeholder management, and leadership—dominated the list, claiming five out of the 10 spots. General business skills and deep work skills (skills that require the ability to focus intensely without distraction) claimed two spots apiece. Top 10 Skills for Future Procurement Professionals

Top 10 Skills for Future Procurement Professionals

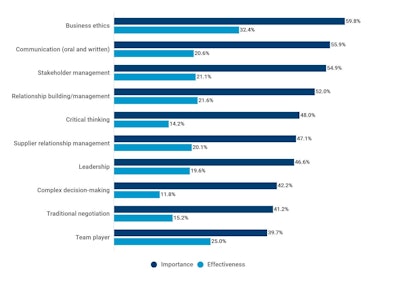

With credentials falling short of expectations and few universities offering degrees in procurement or sourcing, organizations will need to develop these skills in-house. But when APQC asked procurement professionals about their effectiveness in training and developing each of the top 10 skills, we identified sizable gaps. There’s a double-digit gap for each of the top skills between importance and performance, and some gaps are particularly notable. For example, almost 60 percent said business ethics is a critical or very important skill, but only one-third said they are effective at helping employees develop this skill (Figure 3). Gaps for Top 10 Skills: Importance vs Effectiveness

Gaps for Top 10 Skills: Importance vs Effectiveness

The consequences of not addressing these gaps are huge. If organizations cannot develop these skills in-house, they will be forced to secure them through external hires and/or consultants. But the only other option is to simply not develop these skills—and that’s even more dangerous. Organizations may be able to rely on a handful of experienced procurement professionals for now. But when those people retire—and they will—the function will be in the hands of people who never learned how to lead, think critically, or act ethically, and who have never built relationships with key suppliers and internal stakeholders. Clearly, the time to act is now.

This article is part one of a two-part series on the skills gap in procurement. Next time, we’ll discuss how organizations are getting it right—and where they’re falling short—when it comes to realigning talent development with skills future procurement professionals need most.