For the last 10-15 years, China's prominence has grown in manufacturing. Foreign direct investment (FDI) continues to flow inward, albeit at a slower pace today. Exports continue to be an important driver for the economy but are rapidly giving way to local consumption. As with any maturing country, and in particular those that have reached their peak during an industrial revolution – China reached a high of 12.6 percent GDP growth in July 2007 –costs become an important catalyst to curb escalation.

In China, it is clear that costs are on the rise. In early 2008, 70.6 percent of exporters raised their prices, raw material prices rose 9.8 percent, and China's commodity price index increased 9.5 percent year-to-year. With these considerations and other such as quality variability, some companies have begun to relocate their supplier base closer to operations in the United States. Alternative locations for production and sourcing have also fueled a rise in global competition.

With any transition in the supplier base, important variables in the upstream supply chain change. These include service level, lead time, inventory positioning, capacity, and direct and indirect costs. As the world's supply chains continue to evolve, scenario modeling must account for these adjustments. In China, very few suppliers have the capabilities and knowledge to detail how these shifts may affect profitability. Alternative sourcing locations create similar complexities. Without such sophistication, inefficiencies are undoubtedly created, as are significant costs and environmental impacts.

Recent Cost Trends for Chinese Manufacturing

One area of concern until only recently has been increasing labor cost pressures affecting Chinese manufacturing. In 2006, a survey by Hewitt Associates and the US-China Business Council suggested average salary rates increased by 7-10.6 percent in cities such as Beijing. In a 2008 HSBC study, average annual salaries in manufacturing had increased by 105 percent from 2000-2006. More recently, labor cost pressures have subsided from the dramatic climb earlier in the decade. This is primarily due to increasing turnover created by the economic downturn and a growing population of graduated students finding employment difficult. The rising labor cost trend, however, cannot be ignored.

Overhead for facility investment, raw material and machinery are also on the rise. As China develops, areas most sought after, such as Shanghai, are now often seen as too costly. Between 2007 to 2008, real estate prices had climbed by an average of over 11 percent in 70 cities across China. Raw material input prices have rapidly increased, as have production equipment prices. China's production price index (PPI) increased by 7.6 percent in the first half of 2008, but in Q1 of 2009 fell by 4.6 percent. Overall, companies are experiencing lower overhead investment advantages than only five years prior.

Transition to Low-cost Destinations

With these realities, both local Chinese and foreign companies are considering alternative low-cost countries for production. Locations such as Laos, India and Vietnam, in order of export growth between 2002 to 2006, are becoming influential destinations. Similar to China 15 years ago, labor, overhead and production costs are key influences.

Vietnam gained the spotlight with FDI growing by nearly 92.5 percent year-over-year in 2006. With the recent downturn, many companies are altering their investment strategies globally. Asia Pacific continues to be an important focal point. The effect has curtailed the expansion of these countries that were once thought to be competitors to China. In addition, it is here that we begin to see clearly how dynamic global supply chain operations have become.

The Dynamic Nature of Supply Chains

Operations in the west of China and in many low-cost alternative countries are shaped by the supply chain landscape. For example, Laos, a landlocked country that experienced export growth of 50 percent year-over-year in 2006 requires transportation through multiple countries to reach the nearest port. Local logistics influence direct and indirect costs. Inventory holding costs may be lower based on overhead and labor, yet a critical question becomes lead time.

Building on these foundational components, inventory management is clearly an important component. Raw material procurement, especially in alternative sourcing destinations, is different from China. For Vietnam, raw material is often imported, increasing costs. This often creates lower in-transit efficiency. Demand-production synchronization becomes integral through analytical planning.

Another consideration is capacity and utilization. China continues to invest in significant manufacturing, storage and transportation infrastructure. Vietnam is in an earlier stage of development. Smaller geographic and industry sizes, in addition to competition, will impact the capacity and supplier base for localized operations. This influences potential bottlenecks in all four types of inventory.

Assessing Production Location in the Supply Chain Model

With worldwide expansion, companies are only now beginning to consider their supply chain model. This involves production and inventory location. For example, one challenge remaining in China is quality variability. Moving tier-one component inventory closer to finished goods production in another country may be an optimal decision. Major considerations, however, include the relative power of suppliers. For industry leaders, flexibility is key. Strategic balancing between China and overseas production may be utilized to fulfill adjustments in lead time and service level. It is these scenarios where total cost models can best be assessed.

In other examples, companies continue to move farther inland in China. Intel's recent transition to Chengdu, in Sichuan province, is just one example. These decisions are primarily based on lower labor and overhead costs, along with tax incentives. Production and inventory placement is again of primary concern. How do these location transitions affect upstream, downstream and the overall service level?

Assessing Inventory in the Supply Chain Model

Few industries actively concern themselves with minimizing inventory, the automotive and electronics industries historically being classic examples. In China, as well as other low-cost alternatives, the costs of holding inventory greatly influence upstream profitability. Inventory management knowledge is still in an early stage of development.

For all companies, the cost of poor supplier inventory management is tangible. Product recalls, for example, are often a result of material input substitution. If a manufacture faces a stock-out, they will select a supplier that can fulfill the order based on cost. If the component is used without testing, the result may be a recall. The reality remains, when you buy a product, you buy the supply chain.

As with production location, the positioning of inventory is critical. How many companies actually track the inventory levels of their supplier's suppliers? In the case of China or alternative sourcing locations, upstream inventory placement is an influential determinant in lead time and service level. Production delays may result from such conditions in the supplier operations.

The challenge becomes more involved as we map a company's global operations. When a new supplier or warehouse is added, how is global inventory readjusted both upstream and downstream? If a reduction in capacity occurs, how does the lead time and inventory placement change? Unfortunately, software solutions cannot foresee such variables. Inventory is often an afterthought, yet these costs significantly impact profit and cash flow.

Trade Off Between Visibility and Flexibility

An interrelated and important discussion must be addressed as it concerns visibility and flexibility. Visibility is commonly associated with technology-assisted material flow monitoring. In China, as with other developing countries, such technology at the supplier level is limited. Complete visibility requires more traditional methods, namely communication.

In an effort to increase visibility, companies implement software systems to assert control over critical locations. Once manufacturing and distribution locations are fixed, it is difficult to influence change. This significantly limits flexibility to make inventory placement adjustments, which may lead to lost opportunities for cost savings. This is often where local competitors gain a competitive advantage.

Companies in China are currently assessing this balance. In many cases, it is here where investment is being funneled. For some, the growth of localized and decentralized operations during China's exponential growth has led to limited visibility. There are clear opportunities for consolidation, which will reduce redundant costs and the environmental impact. For many, high visibility and control has led to conceded market share. These companies are now reengineering their supply chain framework to localize less-critical operations.

Building a World-class Global Supply Chain

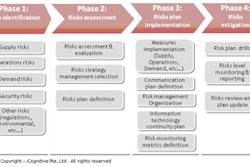

In order to remain nimble yet efficient, companies must integrate simulated models that account for the supply chain architecture within which they operate. These models should account for not only demand and production shifts, but also forecast inventory flexibility as key components of the supply chain change. With the further expansion of global supply chains, cost influences can change dramatically and quickly, influencing inventory holding costs, in-transit logistics, lead time and the service levels. Creating such dynamic coordination is critical to long-term sustainability.

With alternative sourcing locations, "low-cost" hopping and expanding supplier networks, the complexities increase. For some specific products, profitability will be impacted marginally by such transitions. For others, total cost models may show cash flow to be negative. Strategic tools that do not account for such variables can create significant inefficiencies in the supply chain design – the results of which may only be realized when it is too late.

Recent trends in the automotive sector clearly indicate the need for increased flexibility and coordination in production, capacity and inventory. Numerous automotive companies suspended production in reaction to demand slowdowns. A forced line stoppage is a reactive measure. In a clear signal of continuous improvement, Toyota, a symbol of the just-in-time (JIT) model, is moving away from its roots to reposition inventory due to such circumstances.

In order to remain flexible under such situations, all contributors in the supply chain must be informed by scenario planning to appropriately prepare their operations. Without proper management, upstream contributors face the immediate cost of holding excess inventory, which inhibits cash flow. The reverse bullwhip often takes place following such an event, influencing greater delays and downstream costs once production resumes.

With the economic downturn comes an important signal that flexibility and coordination must improve to further reduce operational inefficiencies and unnecessary costs. This importantly includes the entire global network from Kunshan, China, to Reno, Nevada. Those that focus on these key factors now will undoubtedly enjoy a stronger position when the global economy regains momentum and continues to expand.

![Pros To Know 2026 [color]](https://img.sdcexec.com/mindful/acbm/workspaces/default/uploads/2025/08/prostoknow-2026-color.mduFvhpgMk.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&bg=fff&fill-color=fff&fit=fill&h=100&q=70&w=100)