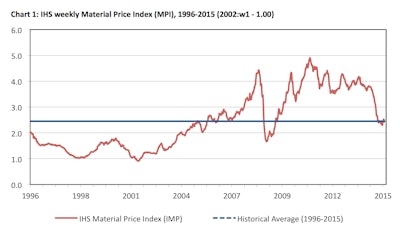

The past 12 months have seen a precipitous drop in many primary commodity prices. Crude oil prices have collapsed, with the price of Brent crude falling from well over $100 per barrel last year to less than $60 earlier this year. Likewise, iron ore prices declined from around $95/metric ton to below $50, and rubber prices tumbled from nearly $2/pound to less than $1.60. Collectively, commodity prices, as measured by the IHS Material Price Index (MPI), have fallen by more than 40 percent since July 2014.

Last year’s commodity crash was not totally unexpected since prices of most commodities had been receding for some years already. The speed of the decline for many commodities, however, took most traders by surprise. The IHS MPI, a weighted average of weekly input spot prices for the manufacturing sector, went into a near-free fall during the second half of 2014. The index had in fact been on a downward path for the prior four years, after having hit its cyclical peak in late April 2011. Since then, despite periodic short-term rebounds, it has generally been trending down and currently stands more than 53 percent below its 2011 peak. IHS believes that the past decade’s commodity boom is over.

China’s role in the current supercycle

While we can blame easy monetary conditions for facilitating the last decade’s commodity supercycle, its key driver was the rapid economic expansion of emerging markets during most of the past two decades. In particular, it was China’s dizzying pace of growth that underpinned the rapid rise of energy and raw material prices. Moreover, it was China’s insatiable appetite for energy, raw materials, and other goods that enabled other developing countries to sustain robust growth for the past two decades. In short, China’s soaring demand for everything from iron ore to oil and gold was the dominant driver of the supercycle.

It is worth noting that China’s ascension to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2002 was a watershed event, without which the supercycle might not have been possible. At a minimum, the cycle’s amplitude and duration would probably have been far smaller. WTO membership not only boosted tremendously China’s exports to the rest of the world, but also attracted huge volumes of foreign direct investment (FDI) into the country’s manufacturing sectors. These, in turn, led to vast amounts of domestic capital being invested in precisely those industries that are intense users of energy and raw materials. The domestic investment binge, which was easily financed by Chinese people’s excessive savings, generated an insatiable appetite for energy and raw materials during the last decade. Indeed, not only did levels of physical consumption of commodities rise, but the rate of their growth also accelerated. It was this acceleration that started to strain commodity markets and pushed prices progressively higher—far above previous nominal cyclical peaks. Commodity prices roughly doubled between 2002 and 2004. They doubled again between 2004 and early 2008, before crashing during the Great Recession’s global credit crunch.

China’s 2008 crash proved remarkably brief, though. The Chinese authorities’ implementation of an aggressive economic stimulus package in response to the Great Recession in late 2008 triggered a frenzied capital spending boom that in turn drove demand for many raw materials sky-high, pushing prices to unsustainable levels once again. For instance, the price of iron ore at China’s Tianjin port climbed to about $200/ton by February 2011, nearly seven times higher than its average during the preceding decade. Even though the vastly elevated price levels were not supported by market fundamentals, for many commodities the boom was sustained by what analysts sometimes refer to as “mania,” or psychological factors. But eventually the day of reckoning did arrive. As China’s economic growth decelerated over the last several years, broad-based commodity price indices ran out of steam. The IHS MPI, along with other commodity price indices, started to sag in 2011—slowly at first, but steadily. The gradual downward trend continued for about two and half years, before culminating in last year’s crash. Even though prices seem to have stabilized somewhat recently, they would likely further decline if China’s economy further decelerated.

What’s next?

IHS contends that most prices have fallen sufficiently for the market to at least find short-term price stability near their current levels. Indeed, when measured in most major currencies, commodity prices have probably already hit bottom.

There are two reasons why further declines will likely be limited:

1. For many commodities, prices are approaching production costs, placing at least a temporary floor under prices.

2. While the global economy’s expansion has been lackluster over the past several years, we do see slow improvement in growth ahead, which should provide some degree of demand support.

So what do these mean for commodity prices? IHS expects any recovery to be fairly muted over the coming quarters, particularly since we believe that China’s economy is set to edge down further in 2016. As a result, excess production capacity in many sectors should constrain price increases in most commodity markets for at least another year. For some commodities, such as iron ore and aluminum, abundant capacity will likely keep prices under downward pressure for some years.

The history of past supercycles suggests that a disorderly price correction, such as the one we have witnessed the past 12 months, usually is followed by a long period of relatively weak pricing power and underinvestment in commodity markets. After a powerful boom usually comes a long, painful bust that discourages investment, but eventually sets up the markets for the next commodity boom and sometimes a supercycle. So the odds are that commodity prices will remain relatively flat for at least several years. Indeed, IHS believes commodity prices will not regain their early-2014 levels for the rest of this decade. After an initial short-term cyclical rebound, real prices might slowly drift higher, but they are likely to remain far below their 2014 levels even by 2025. ■

About the Authors:

Farid Abolfathi is senior director, Economic Risk, IHS Economics and Country Risk.

John Anton is senior principal economist, with IHS Operational Excellence and Risk Management.

John Mothersole is research director, Pricing and Purchasing, with IHS Operational Excellence and Risk Management.