The months of June and July are typically when many large corporations initiate efforts to refine or develop their business plan outlining their goals and associated actions for the next few years. Depending on the company this may be called the "Fall Plan," the "Annual Strategy" or something similar. More often than not it is really just a budgeting exercise with a set of assumptions determined by a person or group somewhere high in the corporate bureaucracy that are passed down to the operating units.

Too often the assumptions are simply some variation of "take last year's figures and add some target percentage for growth" coupled with "cut some target percentage to show we're getting more efficient." The 2010 planning cycle assumptions will be particularly interesting to observe. Given the severe recession and volatility in commodities, currencies and energy, what is considered a normal base to apply those magical target percentages?

A year ago, crude oil was nearly $150 per barrel, which then plummeted to below $40 per barrel and is now over a six-month high at $62 per barrel with demand trending higher. Similar peaks and valleys can be seen across the charts of many commodities and currencies. Some industries and companies have seen demand fall 60 to 80 percent. How do the planners in the corporation decide what is the baseline? Do they take an average? Apply a standard deviation? How do they predict when and how a recovery will take place? Will the charts trace a "V," "U" or an "L?" As Yogi Berra once noted, "It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future."

Accepted Risks of Global Trade

Logistics and supply chain managers have always had elements of risk management in their job description in terms of dealing with an imperfect physical world of severe weather and natural disasters, damaged product, mechanical failures of the shipping conveyance, port delays and, amazingly, even pirates. Cargo insurance, safety stock and back-up plans to re-route freight or use expedited freight are the typical means of dealing with these elements of risk. Considering the complexity of managing a large volume of shipments across multiple lanes, logistics and supply chain managers understand that you can't predict when or where a delay or incident will occur; however, historical data dictates that there will be some percentage of shipments that experience problems. The key to survival is preparation versus prediction.

How can a business prepare for the risks that can't easily be captured based on the history of previous transactions? The last 12 months have been unprecedented. You may have even heard that these challenging economic times have been a "once in a century" or "once in a lifetime" event. Let's hope so. But, is it really true? Maybe the root causes have been different to previous economic crises, but haven't economies had recessions, severe bear markets, high unemployment, and energy price spikes and sell-offs before? And, historically speaking, not that long ago? Yet, how many of 2008's corporate planning assumptions allowed for a wide range of scenarios and outcomes over the coming year instead of a single target number based on a singular view of the future? How many companies will overcompensate their 2009 plans downward in their outlook in establishing that singular view of the future after wildly missing the mark in 2008? That could severely hamper a company's ability to capture the benefits of a sharper-than-predicted recovery.

The Challenge: Recognizing Risks

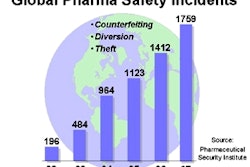

The global supply chain manager has to deal with a wide range of risks besides the imperfections of the physical world. In order to keep product flowing internationally, there are a variety of risks that must be addressed. Export and import compliance are increasingly important as countries are constantly evaluating how to achieve sometimes conflicting goals: how to compete globally while at the same time protecting strategic interests, including the safety and security of their residents. Security and product safety are top concerns for U.S. importers this year due to a recent history of contaminations causing illness and death forcing product recalls and new supplier recruitment. On the flip side, U.S. exporters are experiencing increased regulatory enforcement while at the same time facing the challenges of selling their product into markets where the relatively strong dollar could hamper sales.

Beyond regulatory and security risk the occasional trade war breaks out as a result of national political forces. Some select U.S. exporters have been blind-sided by the Fiscal Year 2009 spending bill signed by U.S. President Obama on March 11, 2009. One of the provisions of the bill was to eliminate that controversial pilot truck program with Mexico that allowed 107 trucks from 27 Mexican carriers full access to the U.S. road network. Per requirements outlined in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) signed in 1994, Mexican trucks should have had access to some U.S. corridors in 1995 with full access by 2000. After years of political opposition in the United States led by various groups, disputes and negotiations with Mexico (including a NAFTA ruling in favor of Mexico in 2001), and another change in political administration, a pilot program was initiated in 2007.

After President Obama signed the spending bill with an earmark aimed at Mexican trucking, Mexico swiftly put in place retaliatory tariffs across 90 products, ranging from onions and potatoes to red wine, deodorant, and telephone handsets. Mexico targeted over 40 states, many with strong Democratic congressional opposition to the pilot truck program, to drive home its complaint. So how do U.S. businesses, many of them small and medium-sized, relying on exports to Mexico with pricing dependent on being duty free under NAFTA, now deal with tariff rates ranging from 10 to 45 percent? How could they have prepared for this risk? What about companies in Mexico relying on importing these products into their stores?

Other political and economic risks that companies are facing with uncertain time horizons include the environment and sustainability. The Carbon Disclosure Project surveyed 500 of the largest corporations worldwide and 80 percent identify climate change as a commercial risk and, interestingly, 82 percent of the same respondents identified climate change as a commercial opportunity. How the current U.S. administration and Congress roll out a potential carbon cap-and-trade program will undoubtedly impact the way businesses and their supply chains operate in the future. Legislation to change corporate taxes on U.S. multinationals operating overseas could likewise directly change the value chain network of many companies. How is your company planning for these types of events now?

The Solution: Identifying, Quantifying and Managing Risks

So far I've risked irritating the reader by raising more issues and questions than providing answers – but asking the right questions is a big part of the solution. What we heard after the U.S. terrorist attacks of 2001 is that the U.S. military had been spending resources by continuing to plan for more conventional warfare against recognizable forces and was suffering a "lack of imagination" with regard to new threats. The recent U.S. financial meltdown has been blamed on "unintended consequences" of a housing bill intended to give more U.S. residents an opportunity to own a home and changes in regulations over the last nine years or so. Don't you think that trillions of dollars of economic stimulus globally just might create some "unintended consequences" down the road? Part of the solution is to systematically think through different scenarios by asking the tough questions.

In scenario planning, focusing on particular outcomes and how your business will react is more important than predicting what precipitated the event. For example, if you trade globally and take advantage of free trade agreements, you may want to think through what your business would do if it could no longer take advantage of the duty free status on that trade lane. You can spend a long time brainstorming and still probably wouldn't come up with a prediction of an earmark in a spending bill crippling your exports to a long-standing trading partner. Conversely, if you import product, how would you address a situation where a trade war erupts and suddenly the product is under a very restrictive quota or a steep anti-dumping duty? Scenario planning goes a long a way in helping your company prepare for a wide range of potential futures. The scenarios will rarely, in hindsight, exactly match the real event, but the exercise of thinking through your response will go a long way toward helping your company react more quickly than your competitors.

Another means of managing risk in a volatile environment is to closely monitor processes and events in the value chain. Over the past several years, companies have been working on migrating business units onto a common enterprise resource planning (ERP) system and "wiring" their supply chain with inventory visibility applications. Some companies are going beyond the typical shipment visibility systems to deploy product lifecycle management solutions that address events extending further back in the supply chain – monitoring how their supplier's suppliers are performing in delivering materials on time. The sooner a problem can be identified, the more potential options a supply chain manager has in fixing the problem before there is serious impact. It's important to remember: information mitigates risk.

Hedging your bets is another method of mitigating risk. If you view major business decisions as essentially being trades that rely on factors such as demand, labor rates, commodity prices, currency exchange and energy prices remaining within a certain range for some period of time, then you monitor the trends of the most critical factors and decide when to exit the trade – establishing a stop-loss in trading vernacular or "folding" as it is known at the poker table. For example, companies in today's environment may view the trend of rising commodity prices, low cost of capital and a potential future of high inflation and decide that a hedge against inflation will be to begin to stockpile inventories of commodity-based raw materials.

Bridging the Past to the Future

One of the more challenging aspects of any corporate planning cycle is to "bridge" to the previous year's plan by detailing what happened since that plan and accounting for positive and negative details from plan to plan. Bridging implies an orderly progression from plan to plan, but this year that bridge may be more of a leap of faith from a previous set of assumptions to a whole new reality. Will you approach the new reality as a single set of assumptions and targets passed down to you from corporate headquarters? Or will your view of the world be many potential realities for which you need to be prepared? As you are going through this year's planning process and the person assigned to your operating unit from the corporate planning and strategy function is asking why you are experiencing so much difficulty bridging from last year's plan to this year's plan in their new Excel spreadsheet template, there is a straightforward, honest and insightful answer that is, once again, a Yogi Berra quote: "because the future ain't what it used to be."

About the Author: John Brockwell has an extensive background in global trade business and process evaluation, logistics planning, and decision support systems. As the Global Supply Chain Management Practice leader in the Global Trade Services business at JPMorgan, his focus is on finding opportunities for businesses to optimize their international trade by improving costs, cycle times and quality and by minimizing risks. A frequenter speaker on the topic of supply chain optimization and impacts to working capital, John was named one of Supply & Demand Chain Executive magazine's "Pros to Know for 2007."