Since 1989, during the National Thanksgiving Turkey Presentation, a presidential pardon is granted to a lucky bird or two. The young tradition is now a fixture of the American holiday and a mainstay festive spot in the news cycle year after year. Still, research says custom dictates that much of the national flightless flock—somewhere in the neighborhood of 50 million—get gobbled up as part of the collective holiday spread.

That’s 50 million turkeys, each worth around $17 in terms of direct industry revenue, but those birds drive an estimated $2.8 billion overall in food spending on a single meal. That’s 50 million birds—fresh or frozen—that need to move from the farm to one of around 64,000 major supermarkets and grocery stores, so they can finally get to 50 million kitchens a day or two ahead of the holiday, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Retailers plan ahead by placing orders for their Thanksgiving bounty, often hundreds if not thousands of birds per store, up to six months in advance. Food product suppliers respond by contracting turkey growers from the world’s largest production facilities down to single-family farms, making sure the expected demand will be met.

The result is that 50 million turkeys are raised, plucked, packaged, packed, frozen, stored, shipped, stocked, shelved and eventually sold. That’s a lot of steps in a complex process designed to ensure that anyone who wants to can eat turkey on Turkey Day. Successful delivery requires the precise interaction of man, machine and technology. And today, the key to increasing the efficacy of the turkey supply chain is how businesses are handling data.

For every turkey that’s on the move in one direction through the supply chain, electronic data is moving back and forth between companies (and certainly within each enterprise as well). From drivers to data, from long- and short-haul truck tires to the tireless effort of information technology (IT) personnel responsible for backend business systems and frontend applications—commerce, goods and information are all tightly intertwined, and every action along the supply chain has an automated digital representation in the form of a dataflow.

Thus, the availability of turkey leading up to the holiday hinges on an extraordinarily complex orchestration in which we see a balance struck between the economics of moving goods and the reliability of business data. But this balance is precarious. And everything, absolutely everything, has to go right.

The IoTurkey Supply Chain

For a long time, information flows across the supply chain boiled down to standardized or structured data—the sending and receiving of business-to-business (B2B) files and electronic data interchange (EDI). However, further mechanization and an explosion of new sources of unstructured digital data are increasing the challenge of securely and reliably integrating information into systems, and moving distributed data across the supply chain network of networks. Basically, all this is pointing to the fact that getting tomorrow’s turkey to the end customer is bound to be a far more data-centric process.

The industrialization of the Internet of Things (IoT) is leading to a data explosion that starts at the farm and ripples outward all the way to the final point of sale. And the importance of not only producing, but also incorporating future-oriented data assets is the possibility of finally increasing logistical efficacy across the entire supply chain—from the earliest point of production until the product is finally in the hands of the consumer.

Farms use wireless digital sensory networks during production to monitor and calibrate temperature, humidity and ventilation, while automating egg turning, hatchery and enclosure sanitation. From there, plants take advantage of real-time event monitoring to track multi-plant production system performance based on forecasted demand—ensuring they’re in sync with expected volume of Thanksgiving turkeys needed. Product output measurement and down-the-line tracking is monitored through digital tagging during early processing.

Distribution centers and warehouses storing turkeys by the thousands then use data for identity and location tracking to predict deliverability windows through onboard tracking and in-time shipping optimizations.

The final point of the supply chain is the supermarket. The end locations use data for real-time insight through combined views of inventory and point-of-sale data to prevent stock outages/overages, and to optimize in-store pricing based on incumbent demand and supply. This real-time insight creates increased avenues for e-commerce purchases in addition to traditional brick-and-mortar outlets—mobile and website-based shopping to get the Thanksgiving meal prepared and on the table.

Do some companies doing business along this dominantly technical version of the supply chain struggle? Of course. These new sources of data point to entirely new points of data generation—the connected machine and machine-like things in the IoT.

Current Technologies—New Capabilities

Organizations need to account for new capabilities that are required in order to handle the striking volumes of data coming from multiple new generation points in the IoT ecosystem. However, much of the IoT heavy lifting can be done by some middleware available today. Managed file transfer solutions, for example, often provide the capability to rapidly add multiple new technology connectors and enable multiple communications protocols straight out of the box, meaning it is easier to incorporate IoT devices into existing systems and business networks.

Fundamentally, the IoT supply chain and data handling come down to an adequate capability for systems and infrastructure to quickly move not just large and small files—think EDI—but to also rapidly ingest aggregate data sets for use in analytics—think Big Data. Still, even without the added complexity of future technology data points, the reality at the moment means a lot of companies are just bobbing for digital apples.

Consistency is essential. Organizations need to build the infrastructure to securely and reliably move and effectively integrate current dataflows, provide critical insight necessary to compete and ready the business for virtually infinite points of data generation just around the corner.

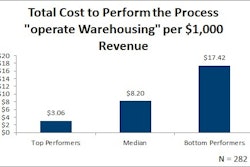

In the highly mechanized farm-to-table logistics operations, it is through better means of moving and integrating the data of today and tomorrow that companies can not only seek to improve, but also actually optimize supply chain efficacy threefold:

- Operate at the lowest possible cost.

- Drive greater reliability in the delivery of products to store shelves.

- Provide the best possible service to customers.

And all of this turkey transit is just a ripple in the massive spend during this holiday week, which includes billions of additional transactions that make the football, flights, floats and—oh yeah—Cyber Monday possible. But that’s a story for another time. In other words, on Thanksgiving, turkey is produced, packed, shipped and stocked in the physical world, but its quality is a wholly digital representation.