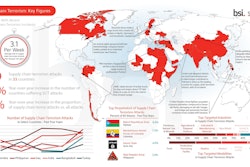

While the fall out of the UK’s decision to exit the European Union has sent shockwaves throughout the political and economic world, Brexit is merely a footnote in the global supply chain risk story. According to the latest CIPS Risk Index, the second quarter of 2016 saw worldwide supply risk reach a level not seen since 2013, with confusion as to the true implications of the move fueling widespread uncertainty and fear. Slow global economic growth, particularly in China, and subdued commodity prices are clouding the picture further.

Short-term protectionist strategies are the order of the day for many companies as they battle against exchange rate volatility, for example. But against this backdrop, a need to address longer-term sustainability issues is being pushed further up the corporate agenda, especially within organizations at the mercy of complex, multinational supply bases. The ongoing and relentless pursuit of low-cost sourcing and efficiency has led to the creation of critical supply chain nodes in at-risk regions. While short-term fear and uncertainty brings unexpected costs and potential disruption, the longer-term implications of failing to tackle sustainability could be catastrophic, putting the very existence of many businesses in jeopardy.

For food and beverage businesses, in particular, the impacts of a changing climate are taking their toll. Extreme weather events, erratic storms, pest outbreaks, drought and disrupted growing seasons continue to put the world’s farmers in an uncomfortable, vulnerable and destabilized position. Their ability to continue to produce the crops companies rely upon is becoming increasingly compromised, particularly in developing countries where smallholder farmers and indigenous communities depend solely on farming to survive.

Take cotton, for example. For every t-shirt made, around 2,700 liters of water is used in the agricultural process—the same amount of water the average human drinks in three years. But, as the World Economic Forum notes, water security is “one of the most tangible and fastest-growing social, political and economic challenges faced today.” The world is likely to face a 40 percent global shortfall between forecast demand and available supply of water in the next 15 years.

There also are a plethora of social challenges posing significant risk to supply chains everywhere. A recent study by Verisk Maplecroft suggests that companies with suppliers in a list of 115 countries have either a “high” or “extreme” risk of slavery, with China and India topping the list. In fact, most companies (71 percent) believe there is a likelihood of modern slavery occurring at some point within their supply chains, according to the Ashridge Centre for Business and Sustainability.

From human trafficking in the Thai shrimp sector, to child labor identified in the Turkish textile factories supplying fast-fashion giants, human rights abuse is a widespread issue, exacerbated by corruption, political unrest and a lack of legal enforcement and governance.

What Can Be Done to Reduce the Risk?

Central to reducing the risk of being exposed to such challenges is having sight of who suppliers are and where they are located. When the Bangladesh Rana Plaza textile manufacturing complex collapsed in 2013, killing 1,130 workers, the scandal of poor health and safety standards onsite was only part of the story. Many companies found themselves caught up in a story of supply chain negligence without even realizing that their products were made at Rana Plaza.

Increasingly, organizations are making use of software platforms to map their supply chain hotspots. By assessing and analyzing data streams to better understand where assets are located, how many employees are working there and associated “risk score” for regions in which the asset is located, supplier engagement or auditing efforts can be prioritized accordingly, helping to avoid the next disruption or risk exposure.

Addressing Supply Chain Transparency

Addressing supply chain transparency is largely ineffective unless companies move beyond the first tier of suppliers. However, reaching out to the many thousands of suppliers that support a business is easier said than done. For example, just half of the 8,000 key suppliers contacted through CDP this year bothered to respond—despite CDP’s analysis showing that suppliers which did report were logging much better carbon reduction improvements and were much better at identifying risk to their organizations than those that did not report.

A growing number of companies are investing in solutions to facilitate better communication between brand and supplier, for example, by initiating a monitoring and remediation system to address child labor in their supply chain. By recruiting and training local agents to work in the field, companies are able to identify children that might be at risk and intervene.

Collaboration also is critical. Because supply chain sustainability is such a complex endeavor, it is not something that can be tackled in isolation. A new survey by the UN Global Compact and Ernst & Young revealed that 78 pecent of 70 large companies interviewed are engaging with non-profits, industry associations, NGOs, and government bodies to initiative collaborative programs. In the apparel sector, for example, the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC), which was formed in 2009 by U.S. retailer Walmart and outdoor clothing firm Patagonia, aims to unify the industry to take a more integrated approach to dealing with some of its challenges. Key to SAC’s approach is the Higg Index, a "standardized supply chain measurement tool" for industry participants to better understand the environmental and social and labor impacts of making and selling their products.

Another collaborative initiative which recognizes the complexity of the textile and footwear value chain is ZDHC (Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals), which has set out a roadmap to phase out hazardous chemicals use by its members by 2020.

In an increasingly complex and globalized economy, where companies continue to seek out efficiencies in parts of the world most at risk of environmental, social and political non-compliance and upheaval, the exposure to a wealth of supply chain risks is unlikely to dissipate any time soon. In fact, the risks are only likely to get bigger, as rampant investor and consumer demand for corporate responsibility, transparency and traceability leaves little wriggle room for non-compliance, malpractice or plain ignorance.