![Figure 1. [Source: The Chemistry of Strategy: Strategic Planning for the Not-Yet Fortune 500, ©John W. Myrna, published in 2014 by Global Professional Publishing Ltd.]](https://img.sdcexec.com/files/base/acbm/sdce/image/2014/06/replacement-product-timeline_11502795.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&q=70&w=400)

Managing risk is a major element of the “chemistry of strategy”—and of successful supply chain management. You must understand strategic risks: what they are, how to identify them, and how to assess and manage them from a strategic perspective. Financial risk is embedded in all these risks, since the impact of all risks is ultimately financial. In additional to managing risk within your company, you need to assess how well your customers and vendors are managing risk. A major supplier or customer who poorly manages risk puts your company at risk.

There are five major sources of strategic risk. Two that have the potential to wipe a company out overnight are:

· Unhealthy concentrations that make a company vulnerable to the loss of a business keystone—a major customer, a uniquely skilled employee, a custom machine, or a single raw material supplier.

· Unpredictable, high-impact events such as a natural disaster, facility fire, or economic crash.

There are three more risks that, while they are unlikely to wipe out a company overnight, could smother it over the next three to five years:

- Superior competitive solutions to the problem the company’s current products address. This could be through replacement technology, integration with another solution, or problem prevention/elimination.

- Insufficient development investments of attention, time, and resources to realize a usable return. An example would be investments that don’t end up creating future products and/or markets.

- Insufficient volume and focus to generate sufficient continuous improvement of products, sales and operations to sustain profitability and competitiveness.

Let’s look more closely at each of these.

Unhealthy concentrations

Managing risk requires you to balance competing demands on resources. Operational needs are immediate and can easily drive an unhealthy balance, with the most obvious risk to revenue coming from an unmanageable concentration (customers, suppliers, product, or market). For example, Acme Manufacturing (company stories are true, but names have been changed) learned that a major customer just filed for bankruptcy. The CEO told the senior executive team, “We’ll have to cover the loss of Groot’s business, and write off more than two months of receivables.”

Acme’s director of operations added: “We also have a sizable inventory of custom parts and raw materials that we’ll have to eat. Groot was 20 percent of our business!”

“But five years ago it was over 80 percent,” said the CEO. “Thankfully, we recognized the risk of that concentration and forced ourselves to diversify our customer base, just in case.”

Acme’s early decision to accept the short-term risk and focus resources on building their business around Groot was rational and the best way to achieve critical mass. However, Groot became such a part of the status quo that for a long time no one thought about the growing risk of depending so much on one customer.

At a strategic planning meeting seven years earlier, Acme’s executive team had identified the loss of Groot’s business as the company’s biggest potential threat. At the time, Acme’s CEO discounted the threat, citing Acme’s regular contact with Groot, excellent quality, and perfect on-time delivery.

In my role as facilitator during that strategic planning meeting, I asked, “What if Groot gets acquired by a company with its own manufacturing supply chain? What if they go bankrupt? There are more ways to lose a customer than poor performance on Acme’s part.”

The Acme executive team established a risk component in its strategy to keep the largest concentration of business under 25 percent, since they felt that any sudden loss of revenue above that percentage would likely be unrecoverable. Acme implemented that strategy several ways:

- Acme became more watchful about maintaining accounts receivables, and more conservative about purchasing equipment and hiring full-time employees to meet growing demand from Groot. Outsourcing work at peak periods reduced margins, but wouldn’t leave Acme with potentially unusable capacity should something happen to Groot. They made sure they never took Groot’s business for granted, and assigned dedicated staff members who were personally accountable for keeping Groot happy.

- Acme gradually shifted priorities and resources to building up a new revenue base. Since Groot was the major player in their niche market, this required identifying an expansion market. Acme established an initial customer base in a new market with attractive potential.

- Acme made sure that everyone in the company understood the importance of fully supporting even small, trial orders from customers in the new market. Without constant reinforcement of why these small “unprofitable” orders were important, well-meaning employees could have sabotaged the new strategy with late deliveries and bad quality.

Unpredictable, high-impact events

Superior Tubing’s Arkansas plant was destroyed by a tornado. Fortunately, the employees were able to get to safety before the tornado hit. A year and a half later, the Arkansas plant had not only returned to full production, the company’s two other plants set new production records. The marketplace recognized how well Superior Tubing managed the catastrophe.

The secret to recovery? Having identified the tornado risk years earlier, they incorporated a disaster recovery program as part of their strategy. They had standardized computer systems across all three plants, making it easy to transfer the working files from the destroyed plant’s backup tapes. They had put plants in multiple locations to reduce the risk of losing one. They maintained sufficient financial reserves to tide them over. Because their employees were already cross-trained to operate a variety of different presses, they were able to quickly redeploy staff, including temporarily relocating Arkansas workers, to expand shifts at the other two undamaged plants.

Superior Tubing’s planning team had felt it was strategically important to integrate recovery into how the company ran, rather than create a plan to recover post-disaster. They regularly manufactured Plant One parts in Plant Two to handle overflow demand. When doing maintenance on Plant Two’s computer system, they ran Plant Two MRP software remotely on Plant Three’s computers. They didn’t wait for an actual disaster to verify that a disaster recovery plan worked. They made their company more robust through an integrated disaster recovery program.

Superior competitive solutions

Best Systems knew it would just be a matter of time before their market evaporated. They manufactured and supplied products based on a computer interface first introduced in military systems over fifty years ago. Their business had grown, based on products that enable military users of legacy systems to build replacement applications that communicate with ships and planes still using this ancient interface. In the short term, Best Systems’ customers are happy to see them continue to develop new and improved versions of their products. However, the military has been executing a strategy to phase out this interface, albeit over decades. Best Systems follows a dual product/market strategy. For their legacy market, the basis of their business today, the company:

- Didn’t waste resources trying to sell products that would require their customer to adopt an old technology.

- Focused product development investments on opportunities with an 18-month ROI and/or features that enable legacy customers to defer their transition to new technology.

- Made every effort to identify and sell 100 percent of legacy technology users.

- Made every effort to motivate competitors to drop out of the market.

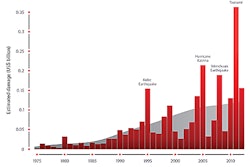

Best Systems’ five-year strategy spotlighted the need to identify, develop, and grow a new business to over 20 percent of total revenue. Given the Product Life Cycle, new market or product sales don’t reach their potential overnight, because it takes time to build a customer base and volume. It might take a product over four years to reach 25 percent of its annual potential. If managing risk depends on sales from a new market/product to replace an expected decline, you must start building that new business years ahead of time (See Fig. 1).

For Best Systems, the smart strategy was to identify and enter the “growth” stage of the new business before their core business entered its “decline” stage. They maintained an open mind about how to obtain that new business, whether by growing it organically or through acquiring a business.

Insufficient development investments

Fun Foods’ business was built on supplying a single product to movie theaters. They sold replacements when their product wore out and made sales to newly built theaters. Revenue plummeted when hard times hit, since no new theaters were being built and existing theaters deferred replacing old products. Over the years, the company had discussed developing additional products for their theater customers, as well as searching for new markets for their product. Yet, when sales plummeted they didn’t have any new products or markets to fall back on. In retrospect, we could see that Fun Foods had never really invested sufficiently in developing them.

Fun Foods was saved by its aggressive acquisition strategy. After a protracted, painful period of downsizing, they acquired a new business which enabled them to survive the decline of their core market. A company’s strategy is a mix of exploration and exploitation. Once exploration has identified major opportunities, successful strategies shift to the exploitation stage. At least once a year, review your company strategy and verify the balance between exploration and exploitation.

Insufficient volume and focus

SWT Services provided three services: staffing, web design, and technical writing. None of their customers purchased more than one service. In effect, SWT Services was three tiny companies under one corporate name. SWT was once the only firm specializing in placing technical writers. Formerly a leader in that niche, SWT now consistently lost opportunities to a local firm that only provided staffing services. By now, their competitor had more assignments in a month than SWT had in a year. Given their low volume, SWT Services started losing money on the staffing service. A small company can’t afford to split its focus. It’s challenging enough to generate a competitive volume within a single niche, never mind three.

Every year, your company, your competition, and your industry can get smarter through an additional twelve months of experience. So, your company strategy must include a roadmap of how you will become more competitive. Each time you move along the Experience Curve, expect to figure out how to spend less to sell and deliver your product. The first time you do anything is the most expensive (in terms of time, effort, money or revision). The more times you do something, the fewer resources it requires, allowing you to produce more results for the same amount of resource. This forms a virtuous cycle—the more widgets you produce, the cheaper it is to produce the next widget. The cheaper the next widget, the more competitive you become, assuming that your company follows a strategy of continuous improvement.

Leaders partner with quality suppliers and service quality customers they judge will be able to support them in the future. The acumen to effectively manage risk is a key element in selecting the best suppliers and customers to bet their company’s future on. In return, the best suppliers and customers will only bet their future on you if they believe you are effectively managing your risks.