Over the past five years or so, the supply chain industry has become painfully aware of how vulnerable product organizations are to supply disruptions. Not only have the majority of these companies experienced a disruption, several public failures have demonstrated the economic damage that can result (e.g. the great Seagate v. WD shift from the Thailand floods). Yet despite the amazing amount of intellectual power and integrated systems in the modern supply chain, there’s a distinct lack of coherence or effective reduction in risk across the industry. Why? Because a true risk-intelligent organization requires a different way of thinking—and an actionable application of technologies.

In short, the biggest risk to the supply chain is not a major event—it’s the lack of clear strategy and process to effectively manage and mitigate disruptions. And we have a perfect opportunity to learn from: a sister industry that went through this process, IT security, to spare ourselves the growing pains.

Supply Chain and IT Security Parallels

Supply chain security looks just like IT did 10 years ago. By 2003, the industry had become an incredibly complex and highly mutable set of nodes, connections, and interdependencies. And like product companies today, organizations were able to tie revenue and economic exposure to this infrastructure. More importantly, it proved just how vulnerable IT was.

2003 was a watershed year for those of us who worked in IT security. While the U.S. government had spent years trying to influence the industry in the commercial market, their language and models were too esoteric to be actionably applied to the commercial sector. But a series of new, highly effective, and highly public worms spread across the Internet in minutes, bringing many companies to their knees. It was the first time the C-suite and boardroom turned to IT with a demand to fix the problem.

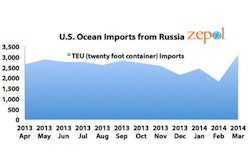

Similarly, the U.S. Departments of Commerce and Defense have tried since 2007 to influence supply chain security with debatable results. It took the Japanese tsunami and Thailand floods to very publically demonstrate the vulnerability and lack of effective supply chain risk management strategies across the world. Now we have to ask the question: how do we really make ourselves less vulnerable?

IT Security Missteps

Following 2003, organizations thrashed around, experimenting with structure and product purchases. Vendors were selling self-defending networks and integrated security suites, while IT was carving off mid-tier managers as security specialists. For the most part, it didn’t work. Many organizations flushed overwhelming amounts of capital in product purchases with dubious returns, pouring op-ex dollars around marginal security changes.

The IT Security Lessons

After about five years, most organizations learned and implemented several changes based on their own pain:

- Security (and risk management) is a shared, yet separated function: There’s a separate organization responsible for monitoring security, but it works with other teams to resolve within the context of the security target (database group, platform group, etc.). There must be a clear delineation between who assesses security and the groups responsible for production.

- Risk management must be part of security: The only way to manage security spending is to integrate business risk and financial context. It’s the lynch pin to triaging decision making, resource allocation, and spending.

- IT risk management & security must be a senior function: Organizations that kept risk and security as mid-tier functions within IT found that security would always take a back seat to production. Humans are naturally bad at making long-term risk decisions vs. near-term monetary decisions. Chief security officers cut through the internal politics and ensured the organization was making reasoned decisions that managed risk and met business ROI requirements.

- Separate but integrated IT security and enterprise risk management: Finance/accounting has long handled enterprise risk management, so it made sense that organizations experimented with integrating the two. Well…it doesn’t work. For the foreseeable future, managing risk, security, and IT requires domain expertise to drive action. Organizations that tried to manage IT risk under finance/accounting discovered an endless theoretical exercise of risk cataloging and frameworks that rarely led to practical implementation. Finance/accounting can help align insurance with risks, but IT security makes the decisions on what to invest in and what not to.

The Center of Excellence Opportunity

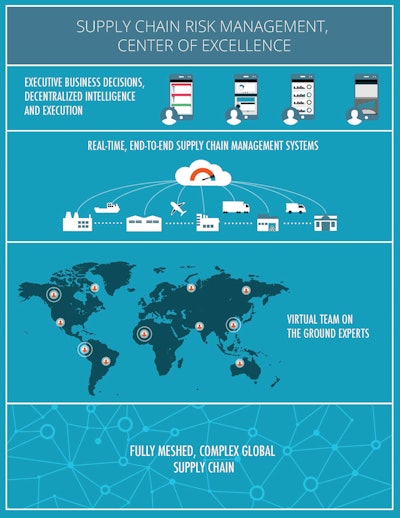

A recent trend across large product-driven organizations is the formation of Supply Chain Risk Management Centers of Excellence (SCRM COE). They are the manifestation of the cross-organizational silo nature of supply chain and the realization that supply chain risk requires a different way of managing your business. Much like IT security 10 years ago, more mature organizations are rethinking and realigning supply chain risk management. These are the best practices of organizations managing billions of dollars in their supply chain:

- Outcome-based risk management: There are an infinite number of risks that create vulnerabilities in the supply chain—it’s the infinite variability that has frozen many organizations into inaction. The new SCRM COEs are concentrating on addressing the finite number of outcomes from those risks. By focusing on a finite problem, executives can make measured, prioritized actions to prevent the highest impact outcomes.

- Executive control: Executive management sets risk thresholds and empowers risk-influenced decisions in sourcing and new product introduction. Their seniority ensures broad adoption and continued focus as the capabilities and processes are developed.

- Integrated risk scope: Organizations measure and manage risk across domains, rather than as independent projects—supplier, production, order, financial, transportation, and operational risks. This taps into employee institutional knowledge to ensure the most well-informed employees are solving the right problem.

- Prediction over resilience: Organizations get past the old way of thinking about how quickly they can respond to an event. They think about risk mitigation in terms of daily supply chain value at risk from a disruption. Organizations then focus on how to proactively identify risk hotspots and reduce the maximum downside exposure.

- Distributed team, dynamic command and control (C&C): Organizations that stood up central SC war rooms quickly learned that they were not only expensive, they spent an inordinate amount of time trying to pull data from the far-flung experts. SCRM COEs are moving to a decentralized, dynamic model—where teams are activated dynamically, based on the type of event—and involves both central business leaders and local subject matter experts. Management can set pre-defined thresholds and allow events to be resolved locally, while corporate resources martial when there is material risk to the business.

- Community view: Organizations stop thinking about supply chains as linear links of suppliers, moving to viewing them as a fully integrated community of intelligence and vital ingredient in the organizations’ success (both current and future). They demand better upstream visibility from their suppliers in exchange for better terms and forecasting.

- Real-time data visibility: Organizations cut out the “data expeditors” and move to automated, real-time, cross-organizational visibility. More importantly, they align these solutions to increase the return of “supply chain signals” and create a truly interactive communication partnership.

The Secure Future of Supply Chain

We are at an exciting precipice in the supply chain industry. If we take the lessons learned from IT security and think about supply chain in the right way, we will end up with a more robust and predictive industry. Executives will make proactive risk decisions in the normal operation of the business, subject matter experts will drive risk mitigation actions with corporate air cover and resources, and supply chains will be built fully cognizant of their own company’s intricacies and worldwide meta trends. It just takes a creative way of thinking.

Dean Ocampo leads the go-to-market strategy for the Exposure risk management solutions as Senior Product Marketing Manager at Elementum. He has helped companies build their security, compliance, and risk programs while serving in product marketing, product management, and consulting roles at several high tech and Internet security companies. He is a Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP).

Dana Martin is an expert in supply chain risk management, serving as Product Manager for risk management solutions at Elementum. In recent years, he's held various consulting roles with government and leading Fortune 500 companies, helping clients develop best practices in supply chain security, anti-counterfeiting strategies, and operational risk management.