From the embryonic to the iconic, companies and whole industries are defined by the intellectual property (IP) they own. In our increasingly convergent world, a startup with one key patent can grow exponentially while mega-companies dominating whole patent classification codes can be displaced and, if they don’t adapt, rendered obsolete.

Investors value the strength of a company’s IP portfolio and its ability to defend and grow it; but it can be a risky business. There is a large and growing global legal industry—both internal legal departments and independent law firms—whose purpose is to engage in the defense and dismemberment of IP. Knowing when to “lawyer up” and when to move on is rarely an easy decision, and even a legal victory is no guarantee of a successful business strategy.

In parallel, companies face the challenge of developing and evolving their IP portfolios: that is, creating an environment or framework in which investment consistently produces value for stakeholders in the form of new products or processes. As with any strategic asset, managing and protecting IP is core to revenue growth and company valuation.

Understanding the evolution of IP and its trajectory can produce insight into how and when it can be leveraged to create new market opportunities—whether in an already-crowded landscape or an as-yet-to-be-defined new product category.

A visual analogy for understanding this evolution is to consider the global patent collection as an IP “forest.” Each “tree” represents a unique product category based on a patent classification code, such as the International, or IPC, code. For example, the code H04Q 7/00 is “selecting arrangements to which subscribers are connected via radio links or inductive links.” This particular product category has seen an explosion of activity due to the growth of cellular communications. Individual product category trees, such as H04Q 7/00, sprout from foundational “seedling” patents that grow with the addition of new patent “leaves.” These new leaves may be derivatives of the original patent or come from other disciplines.

The sprout grows into the market-driven “sunlight”—that is, market demand for products utilizing the IP. As a seedling becomes a “sapling,” new patent leaves are introduced to absorb new market light. As the tree thrives, it matures and the proliferation of leaves produces branches that support growth to new market light. Over time, the lower branches receive less light, becoming backward citations. They are the necessary building blocks that ensure the growth of other branches that are now pursuant of the strongest market light and defining the latest iteration of product innovation.

Mature trees produce seeds that will themselves grow into new trees. Sometimes these sprouts fall adjacent to the parent tree and sometimes they plant their roots in a distant part of the IP forest.

Using the tree analogy, there are three main trajectories for IP development companies can pursue:

- Add a new leaf on the same branch of the tree by filing patents immediately adjacent to one another that result in incremental product improvements.

- Add a new leaf on a different branch of the tree by filing patents that spawn new but related products that threaten exposure to the market light for other patent branches.

- Plant a seedling elsewhere in the forest by filing patents that could eclipse current technology.

Three strategies that follow from these three trajectories will determine a company’s growth and market valuation potential for years to come. To balance the risk, many companies pursue a combination of the three strategies.

Strategy 1: “New leaf, same branch,” or inward innovation

Filing adjacent patents is an inward-looking IP strategy intended to defend, protect, and incrementally grow market share for existing products. For instance, Apple’s introduction of iPhones with colored casings enticed a subset of customers to upgrade.

In truth, defending and protecting market space is largely a litigation strategy rather than an innovation strategy. Indeed, the majority of IP litigation that companies engage in is infringement defense from patents that occupy the same classification code. Companies will defend (or attack) their space on the branch where they currently have the most market light. In many respects, litigation is the default IP strategy, as it is familiar ground. Companies know their products, their competitors, and their markets. Still, the strategy is generally short term, protectionist, and can be more time consuming than finding new branches on the tree or planting seedlings that will grow into new industry trees.

It can also be very expensive. Consider the “smartphone patent wars” between many of the major manufacturers—most notably Apple and Samsung—that continue to rage today over devices that have long since faded from the shelves and out of trendy pockets. Millions of dollars were spent on litigation with very little, if anything, to show for it. Bottom line: the new-leaf, same-branch strategy is market topiary designed to keep the light on what will eventually be a fading leaf on an inner branch. Ultimately, the tree will grow from somewhere else and the market won’t care about the millions spent on litigation.

Strategy 2: “New leaf, different branch,” or outward innovation

If the first strategy is about defending old markets, this strategy is about growing outward into new market light to stay ahead of the competition. There are a variety of ways companies can do this, but the most common is to grow or switch to a new branch: for example, the introduction of IP to wirelessly charge mobile phones, which can be traced back to a US patent granted to Nikola Tesla on May 15, 1900.

From observation, only a small percentage of companies are effective at consistently evolving IP into new markets ahead of the competition. The rest are fast followers that enter the market and file incremental patents prompting the early movers to move on again before the market becomes commoditized.

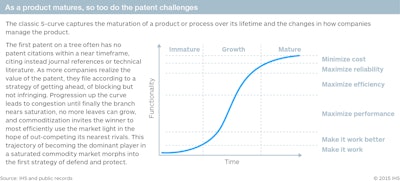

Of course, timing the next move is critical. Understanding where the market is on the life cycle maturation curve—the S-curve—can be helpful, as it often corresponds to the density of patent filings: that is, the more patent applications, the more mature the market (see figure below).

[image: IP Article_Figure 2.jpg]

Companies know this and develop IP strategies to stay ahead of the commoditization trap. First movers will harmonize their R&D spending to find the path outward into new light-filled areas, while fast followers track them to ensure they will be the next leaf growing in the new space. The alternative—or complementary—strategy for the market leader is to stay and fight to protect its market position on the branch. This, of course, is the inward-looking new-leaf, same-branch strategy.

Consistently finding and timing the path outward is not easy. For those that do it well—Procter & Gamble, Qualcomm, and Schlumberger, to name three—it has become part of their corporate culture. This includes incentives to file ideas; fast communication paths to legal departments; public recognition of employees for inventiveness; recruitment strategies that include criteria for developing patent portfolios; and providing employees with time to pursue value-added activities outside of their day-to-day responsibilities.

Strategy 3: “Plant a new tree,” or forward innovation

The list of innovative companies that develop IP that launches a new product classification is the shortest of the three. Edison, Ford, Sony, Toyota, and Apple are iconic examples. While Apple did not invent the smartphone, its IP refined and defined it. Likewise, Toyota built on earlier battery technology to plant the electric vehicle (EV) powertrain seedling in the 1990s. The first leaf was the hybrid Prius, which hit the Japanese market in 1997. Since then, Toyota has filed thousands of patents to protect and grow the EV powertrain tree just as other automakers have entered the market with their own hybrid EVs. Today, the tree has a number of branches, including the plug-in hybrid electric vehicle, mild hybrids, full hybrids, and hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles. Combined, these EVs accounted for nearly 3 percent of vehicle sales worldwide in 2014, according to IHS.

Of course, planting a new tree does not guarantee success. Consider, for example, a display manufacturer that recognized user frustration from relying on touch as the interface for mobile devices. The company launched an R&D effort to develop fingerprintless coatings that could be fused to the glass or added as an aftermarket add-on. However, a disruptive technology that makes touching the screen altogether unnecessary emerged shortly after, and the company’s ability to capitalize on its investment is now uncertain.

It all comes down to critical thinking

It is often the case that an incoming technology resolves a constraint that the adopting market had not. The constraint may be one of manufacturing or material properties or something else. It can often be recognized as addressing not the wants the consumer has articulated, but the needs they couldn’t. Of course, hindsight is 20/20 so, looking back, the answer always seems obvious. But why is it not obvious when companies are peering forward? This is the question every executive asks. The decisions made at this level have direct shareholder impact, with percentage points of market share and valuation gained and lost not just on the decision, but on the long-term course for the company set from that point onward.

It could be said that top-tier global companies are better at making these decisions. Indeed, they execute the decisions sufficiently fast to stay on the part of the tree that receives the most market light or plant seeds in the most fertile parts of the forest. But where does this insight come from given that the majority of information is widely available? Indeed, the same advisors and consultants are offering their services to a wide array of companies.

In nearly all cases, the first step—the most important step—is to think critically. This requires companies to be ruthlessly objective when analyzing technology options, the dynamics of the market, and a thousand other factors that often are ignored. The best decisions for forward growth are based on addressing the questions about the unknowns, not the knowns. They deliberately force conventional thinking to be unconventional and, more often than not, aim to disrupt and compete with their own technologies, not just those of their competitors.

By setting a critical-thinking framework with which to drive innovation, companies can embrace the cultural process and grow more efficiently; build sustainable, defensible, and diverse IP; and ultimately create the most value, be they embryonic or iconic.

This article is excerpted from the original article that appeared in the Q1 2015 IHS Quarterly. The full text—including case studies—can be found at on ihs.com/PatentTrees.

[filler imagery, if needed: reference Stock Imagery Suggestions.pptx, slide 5]