Cambodia’s economy has come a long way from the utter devastation of the civil war era: the country is now the world’s 10th largest garment producer as cheap labor and foreign direct investment-friendly policies facilitated the development of a vibrant garment manufacturing sector. Cambodia’s manufacturing success is not exclusively the result of domestic structural changes, it reflects broader changes in Asia’s manufacturing landscape and the ever intensifying search for low-cost manufacturing opportunities. This report examines the rise in the Cambodian manufacturing, the underlying factors behind its improving competitiveness, and

the challenges ahead.

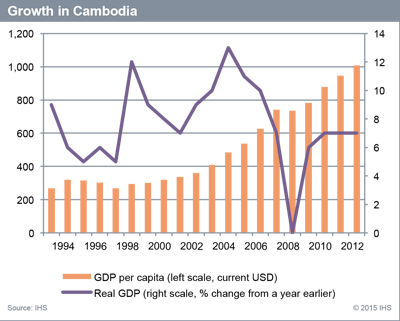

Cambodia’s economy has transformed in a remarkable fashion over the past two decades. Economic growth has been rapid, although quite volatile, since the early 1990s, as the country transitioned from a central-planning system to an open-market economy. Occasional political uncertainty and major external shocks, such as the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the global economic recession in 2008, have driven the volatility in economic growth, but Cambodia’s economy weathered crises well and recovered quickly. Real GDP growth has exceeded 5 percent in most years—reaching double digits from 2004 to 2007—then dropped drastically to zero in the wake of the global recession in 2009 before recovering quickly to 6 percent in 2010.

Trade became a major impetus for growth for the small domestic economy, as a result of policy-makers’ savvy reforms aimed at gaining access to far larger markets. In 1993, total merchandise exports were $284 million (U.S.) and accounted for only 11 percent of GDP. By 2013, exports jumped to $9.3 billion (U.S.) and almost 61 percent of GDP, reflecting the significance of trade in overall growth, but also an increased dependence on external demand.

Restored political stability following two decades of civil war and a reorientation towards a market economy helped launch the garment industry in the mid-1990s. Cambodia benefitted from quota-free access to the United States, while many traditional regional manufacturing bases, such as China, were quota constrained at the time. Additionally, having gained preferential access to the European Union in 1997, further facilitated access to key markets and well positioned Cambodia as an attractable hot spot to many garment investors.

Throughout this period of robust economic expansion, the country’s per capita income more than doubled in amount, but Cambodia remains one of the poorest countries in the world, with per capita income just reaching the $1,000 (U.S.) mark—a level comparable with Bangladesh and Myanmar. The country’s economic base is extremely narrow, with rice dominating the rural economy, and garments the manufacturing industry.

Composition of Cambodia’s manufacturing sector

Manufacturing exports dominate as the major commodity group exported since 2000, with their share in total merchandise exports averaging over 90 percent. Agricultural exports are the second biggest commodity exported averaging 4 percent, and fuels and mining products are the smallest group, accounting for less than 1 percent throughout the period. Production is highly concentrated in a low-value-added sub-sector, as garment exports represent the largest commodity exported within manufacturing. The dominance of garment exports, which averaged more than 60 percent of total exports throughout the past decade, has made the economy particularly vulnerable to sector-specific price and demand shocks.

At present, Cambodia’s garment sector operates on the final phase of garment production, which encompasses cutting and making yarns and fabrics into finished garment products and where value added and profit margins are relatively low, which supports growth to an extent, but also represents a limiting source in the potential growth going forward. In producing these finished products Cambodia relies almost exclusively on imported materials, given the lack of a domestic textile industry.

Drivers of Cambodia’s competitiveness, comparison with other rivals in region

A number of factors, within and beyond Cambodia’s borders, are responsible for fueling the country’s burgeoning competitiveness as a regional manufacturing hub. Rising wages in China and Southeast Asia undercut the competitiveness of the major traditional manufacturing centers and allowed emerging markets, such as Cambodia, to gain market share in price-sensitive segments of the industry. As a result, many multinational companies have responded to the changing regional trends by shifting their investments from their principal offshore manufacturing platforms to frontier economies such as Cambodia.

Low wages, a favorable geographical location, and a benign demographic profile helped grow Cambodia’s manufacturing base. Cambodia’s workers have one of the lowest mandated minimum wages in the region, which helped lure manufacturing companies looking to locate or relocate their businesses. Adidas, GAP, and H&M are only a few of the many major global clothing brands that have moved production to Cambodia in recent years.

Two rounds of large minimum-wage increases in neighboring Thailand in 2012 and 2013 increased labor costs substantially there, which had a positive impact on Cambodia’s relative competitiveness as a production center. In 2014, the Bangkok Post reported that TK Garment, a leading original equipment manufacturer for Thai fashion lines, relocated its largest production site to Cambodia to avoid higher wage costs.

Another important factor driving Cambodia’s garment industry edge lies in the government’s FDI-friendly policy and the number of tax incentives it offers to garment investors. Except for land ownership, Cambodia treats domestic and foreign investors equally, and 100 percent foreign-owned firms are also allowed. Some of the incentives include a 100 percent exemption from export tax, 100 percent import duty exemption on construction materials, production equipment, intermediate goods, and raw materials for export-oriented goods.

Outlook and implications

Cambodia’s garment industry is an export-oriented industry in which most of the garment production is destined for export. Although Cambodia has secured a strong global presence in the manufacturing industry, its exports remain narrowly based and only concentrated in a few markets—the U.S. and the EU. The dependence on a few major markets has left the economy vulnerable to changes in external shocks, which was experienced in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008 when Cambodia’s growth dropped to zero percent and the export demand plunged. The demand recovered quickly from the United States and the European Union, but this experience is a strong reminder of the importance of economic diversification and development of a broader range of export destinations.

Given the lack of domestic textile industry, which would allow for more integrated production processes and an increase in the domestic value added, the focus in low-wage, low technology production could compromise Cambodia’s export competitiveness, if the country fails to upgrade its industrial base. The high concentration of production in the garment industry represents a constrain in achieving higher economic growth, and diversification towards higher value and more technologically advanced products away from labor-intensive industries remains a crucial challenge for sustained growth in the medium and long term.

On a positive note, an increasing number of Thailand-based Japanese companies are now looking to take advantage of lower production costs and expand their activities to Cambodia in auto parts and electronics, which could prove to be beneficial for the diversification of the manufacturing base beyond garments.

For example, Japanese auto-parts makers Yazaki and Sumitomo Wiring Systems have recently announced their decision to shift some of their production sites from Thailand to Cambodia.

In order to accelerate diversification and improve competitiveness in a changing global trade environment continued improvements in human capital, including through education and training, infrastructure, and the business climate are needed. ■