Transportation spend is the second highest supply chain cost businesses face, second only to direct cost of goods themselves. It is the highest indirect cost. Margins are decreasing everywhere as supply chains expand and twist in complicated and expensive ways around the globe. Demand is more volatile than ever, and we cannot rely only on traditional sales & marketing efforts to maintain growth. Today’s leaders are looking to supply chain expertise as a means to differentiate their offerings and enhance customer experience. This paradigm shift is driving supply chains to become more agile, responsive and risk-proof while keeping discipline around cost and overall supply chain efficiency.

Despite transportation spend being such a huge cost factor we have seen very limited effort to reduce it, primarily because transportation spend in most organizations gets distributed across multiple silos. Organizations have looked to transportation management systems (TMS) to address transportation spend within these silos. A TMS automates transportation processes and tries to find the most cost-effective ways to transport goods from one location to another. But traditional TMS technology imposes limits on how much cost we are able to take out and does not even begin to address supply chain agility and responsiveness requirements.

Traditional TMS operates in silos inside individual organizational boundaries or geographic regions. The technology and information model renders it incapable of cutting across divisions, whether those divisions are internal (between sourcing, transportation operations and accounts payable), regional (between states, countries, or blocs), or external (between suppliers, logistics providers, and carriers).

What does that mean for transportation spend?

Traditional TMS creates small pockets of savings, but it doesn't reduce costs across the entire supply chain. The silos create conflicts of interest between parties. For example, sourcing optimizes for reliability while finance focuses on cost. Silos create costly blind spots where goods are invisible and out of direct control. It’s practically impossible to adjust to any sudden events that might occur, like a natural disaster, political turmoil or a sudden demand change.

Traditional TMS was supposed to tackle the huge problem of transportation spend, but there wasn't the technological capability to make it work. However, two major shifts are changing the face of global transportation management as we know it:

1. Supply chains are becoming increasingly complex, relying on partners and data beyond the four walls of the enterprise.

2. The very definition of global transportation management is broadening and expanding well beyond the traditional TMS scope.

As a result, several new initiatives will move to the forefront of transportation strategy:

Creating a common foundation for the agile supply chain

When companies expand organically or inorganically, they often work with new suppliers, serve new regions, and sell to a more diverse set of customers. New customers have different needs and expectations, and expansion usually results in a more diverse and complex technology footprint. The result is an extremely complex supply chain – one that is tasked with keeping up with the unpredictable, unexpected surpluses, shortages, and demand volatility inherent to today’s global markets.

How do you maintain control in such overwhelming market conditions?

The strongest supply chains are the ones that are the most agile. The ability to make quick adjustments based on fluctuations in supply and demand can help avoid disruptions, maintain profitability, and set a manufacturer apart from the competition. It is a complex and challenging problem. Companies today need a foundation for connecting different parts of their supply chains.

Using communities to bridge partitions

Enterprises, large or small, require structures to address their functional needs, take advantage of different skill sets people bring, expand geographically, or grow into multiple product lines. This evolution creates natural partitions within an enterprise to function efficiently. As organizations grow, these structures grow in complexity and partitions lead to barriers restricting information flow across an enterprise. This impacts procurement, warehouse management, transportation management, demand planning, inventory planning, supply planning and other functions. The transportation management function itself may be partitioned by geography, business unit, mode or the part of the supply chain it addresses. Most of these partitions are essential for efficient functioning of an organization.

Multi-enterprise business processes add another dimension to this structure. For example, a company’s supply chain extends into other organizations for its strategic, operational and information needs. In fact, today’s supply chain draws close to 80% of its information from outside the enterprise. These supply chain partners – suppliers, manufacturers, logistics services providers, transportation carriers, financial institutions – play different roles in a global supply chain. These organizations have different interests and partitions between them and are often more likely to create barriers. All the same, they need to share information and collaborate with one another to build a successful supply chain.

Focus on customer experience from a global view of Supply Chain

Customer experience was not a focus area in years past but is widely considered a competitive differentiator today.

There are different interpretations of customer experience. A manufacturer used to associate it with all the items on an assembly line reliably showing up together. A retailer thought about it in terms of the shelf being stocked or a customer getting a package delivered to his or her home on time and in good condition.

This definition, and customer expectations, have expanded substantially over the past few years. It starts with the ordering process when a customer expects a reliable projection of when the product will be delivered along with options for changing the delivery schedule. Customers also expect to receive updates at every stage, whether the estimates change or not. A big part of customer experience, most commonly overlooked, is our ability to manage exceptions. Keeping to the schedule is as important in these cases as communicating with the customer.

Fulfillment process for a consumer order in today’s omni-channel supply chain is complex. This complexity goes all the way from the store front to the distribution center and back through the supply chain. Fulfilling an order can take anywhere from 5 to 15 handoffs. Exceeding customer experience requires each and every part of the supply chain, irrespective of the group and its role in the process, to operate the same way and on a common platform.

Managing all domestic and international transport together

Today’s transportation management systems are specialized and largely geographically limited, mostly managing land based transportation within North America or Western Europe. Other geographies, including Asia-Pacific and South America as well as international transportation, have not been the focus of transportation managers or TMS applications. There is general agreement on the need to address these gaps to enable agile and responsive supply chains. Various large enterprises, logistics service providers, and industry analysts see the need for a single "ubiquitous" logistics network in which an organization can plug in once and have access to any and all of its partners and information.

Many TMS system providers advise first to focus on domestic. What does domestic actually mean? Transportation operations in North America, Western Europe, South America and Asia-Pacific have very different requirements. Most of the applications focus on the domestic US geography while a smaller number is able to address Western European operations with some limitations. They are operating in silos. Even when they address the functional requirements of other geographies, they stay too expensive to justify an implementation in a silo. These gaps highlight the need for a single view, connecting all domestic and international transportation through a common foundation.

Redefining TMS

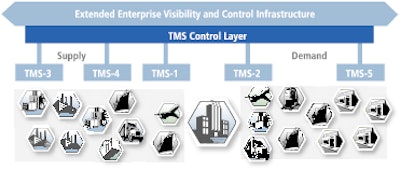

The key to this broader global approach to TMS is placing an end-to-end supply chain layer that all existing applications can plug into. This delivers a single platform for sharing and viewing all data, regardless of region or mode. The data is integrated and each executive can view and use the information in the required format. Most importantly, different messages from other partners and supply updates from carriers or suppliers are captured. Anything that’s happening in the supply chain that impacts a customer shipment resides inside that unifying layer. This is true end-to-end visibility through a supply chain control tower.

The difference in this approach is that companies don’t have to build or standardize or replace applications and partners. There’s no forced standardization of processes requiring a local or regional approach. TMS in a cloud-based layer brings together all supply chain applications and partners and integrates the data flow to empower all users. Barriers that once existed around international and domestic transportation become a thing of the past. Silos between regions, departments and parties are dissolved – replaced by a single global view—and a new kind of TMS, a global TMS, can take shape.